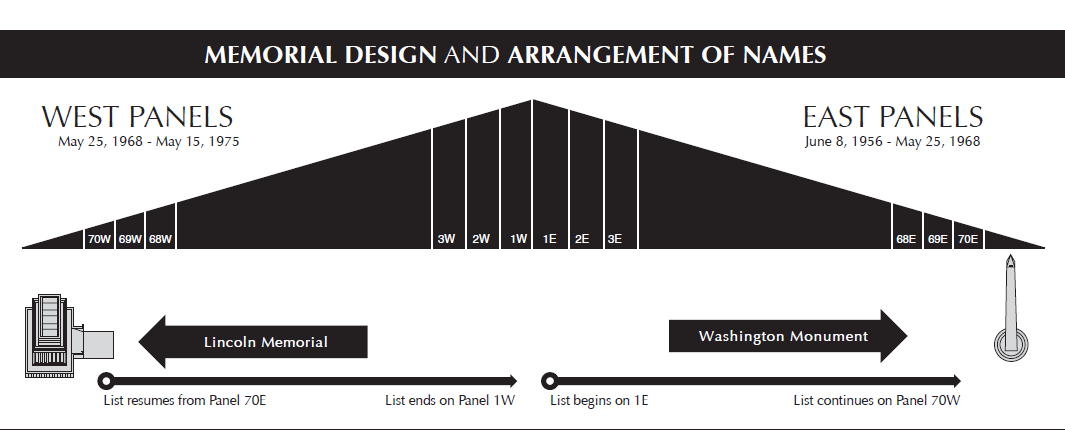

The history and controversy of when the first names on ‘The Wall’ begin is a very interesting one. To this day, there is still conflict on what date the names on ‘The Wall’ should begin. But it is important to note that the names are listed by casualty date, starting at Panel 1E, at the apex, flowing from top to bottom of each panel out to Panel 70E. The casualties continue onto Panel 70W and flow back to the apex, ending at the bottom of Panel 1W. Since there is limited space for adding names, we usually try to add names around the time period of their casualty. Sometimes this does not always work out as such.

The first American to be killed in Vietnam is COL A. Peter Dewey who died September 26, 1945. His name is not listed on ‘The Wall.’ When ‘The Wall’ was in design stages, the DoD provided documentation starting with January 1, 1961, SP4 James T. Davis’ death [Panel 1E, Line 4] . Noted to be “the first American killed in the resistance to aggression in Vietnam.” by President Johnson. It wasn’t until 1999 when TSGT Richard B Fitzgibbon III was added [Panel 52E, Line 21]. Fitzgibbon was murdered in Vietnam on June 8, 1956. Thus, officially pushing back eligibility to be added to ‘The Wall’ to November 1, 1955, when President Eisenhower activated MAAG (supported by Sen Ed Markey’s acquisition of this post’s featured photo when the French left Vietnam.)

RESEARCH IS ONGOING ABOUT THE BEGINNING NAMES ON ‘THE WALL’…

The Heroes: 5 Miles for 5 Names

LCPL Richard B Fitzgibbon JR

According to Colonel Johnson:

“Our MAAG C-47, on which “Fitz” was crew chief, had returned from a trip to Hong Kong at approximately 1300 hours on Friday, 8 June, after an uneventful flight. When all the passengers had deplaned “Fitz” and the other members of the crew went about their normal maintenance duties, readying the aircraft for another flight the following morning.

When his work was completed, “Fitz” left the airfield for his quarters, in downtown Saigon, for a well-earned rest, a shower and dinner. As far as is known, he planned a quiet evening, relaxing and resting up for the next day’s flight.

That evening, at dinner, an incident occurred while “Fitz” and several of his friends were eating at the Non-Commissioned Officers Club. SSGT Edward C. Clarke, the radio operator on Technical Sergeant Fitzgibbon’s crew, walked into the club and stood several paces away for a time, watching and glaring at “Fitz.”

Shortly, “Fitz” got up and walked over to Clarke and according to observers they had several moments of what appeared to be rather heated conversation. Soon after Sergeant Fitzgibbon returned to his table, someone in the group told a joke and the entire group laughed. With this, Sergeant Clarke walked up to the table and said “you had better stop talking about me.” Sergeant Clarke, without another word, turned and departed the club.

After eating, “Fitz” left the club and walked the several blocks to his quarters. No one knows just how long it took Sergeant Clarke to cross the thin line of sanity that the MAAG First Sergeant spoke of. No one saw him return to his quarters and remove a .22 calibre target pistol from his locker. Nor did anyone give Clarke more than a glance when he presumably returned to the NCO club only to find Sergeant Fitzgibbon had returned to his quarters.

At 2145 hours Richard Fitzgibbon was in front of the enlisted billet where he lived. He had been sitting in a chair that he would customarily remove from just inside the doorway after every return trip from Hong Kong. Minutes earlier Vietnamese children had been crowded around him. “Fitz” wouldn’t let anyone chase them off. After all, he had gotten to know most of them and after a trip to Hong Kong they flocked around him as was customary. The sun had just set beyond the buildings — Vietnamese women were just taking in the last of the wash hung from the balconies. Most of the children were on their way home. The gray haze just before darkness almost obscured Staff Sergeant Clarke as he approached.

“Fitz” lived directly across the street from me,” said Master Sergeant Burroughs. “I was in my room with a couple of friends polishing off a jug when we heard two series of rapid fire — at that moment it sounded like fire crackers, but immediately someone reported a shooting.”

Clarke had shot “Fitz” five times at close range.

Immediately afterward, Clarke walked into a bar next door, and without a word shot and wounded SFC John Sakmar, an Army Sergeant, also assigned to MAAG. Sakmar was shot three times. “I looked across the street and noted something was wrong,” said Burroughs. ” We had a medic upstairs so I had someone grab him and a first aid kit.

“After shooting Sakmar, Clarke left the bar, gun in hand, and proceeded up the street,” said Johnson. “When the local police attempted to stop him, he ran into a building, went upstairs and positioned himself on a small balcony overlooking the street. The police opened fire on Clarke who slipped and fell to his death on the sidewalk below. He died as a result of the fall. He was not hit by police bullets nor did he shoot himself.”

CAPT Harry Griffith Cramer

CAPT Harry G. Cramer Jr. was a Special Forces qualified infantry unit commander assigned to the Mobile Training Team, 14th Special Operations Detachment, 1st Special Forces Group, MAAGV. On October 21, 1957, CAPT Cramer was conducting an ambush drill in a field near Nha Trang. A Vietnamese soldier near Cramer was readying to throw a lit block of TNT when it prematurely detonated. The TNT was later determined to have deteriorated in storage and was unstable. Cramer died instantly and other members of the team and their students were wounded. He was considered the first U.S. casualty of the Vietnam War. His name was added to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial Wall in 1983. [Taken from coffeltdatabase.org and wikipedia.org] (WKillian, vvmf.org)

MAJ Stanley M Staszak, Repatriated in 2015

Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) were U.S. military advisors sent around the world to assist in the training of armed forces and facilitate American military aid. During the late 1950’s, as the communist insurgency intensified in South Vietnam, the U.S. increased its number of advisors in the country. Most served in low-ranking positions advising the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). On April 4, 1959, a MAAG advisor serving at the Vietnamese Military Academy, MAJ Stanley M. Staszak, died unexpectantly in his sleep in Saigon. His remains were transported to the U.S. Air Force Hospital at Clark Air Force Base in the Philippines where postmortem studies determined he expired from coronary thrombosis (blood clot in the vessels or arteries of the heart). Staszak was 39 years old. He was buried at West Point Military Academy. In 2015, his name was added to the Vietnam Veterans Memorial wall. [Taken from coffeltdatabase.org] (WKillian, vvmf.org)

LCDR George Wood Alexander

On Wednesday, February 17, 1960, a Douglas R4D-5 (DC-3) from Naval Advisory Group, Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) was on a flight from Saigon to Hue when it crashed into Hon Chay Mountain, a 2,752 foot (839m) mountain peak near Da Nang, Quang Nam Province, South Vietnam. All three crew members were killed. They included LCDR George W. Alexander, LCDR Roger H. Mullins, and ATC William M. Newton. [Taken from aviation-safety.net and other web sources] (WKillian, vvmf.org)

LCDR Roger Hugh Mullins

On Wednesday, February 17, 1960, a Douglas R4D-5 (DC-3) from Naval Advisory Group, Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) was on a flight from Saigon to Hue when it crashed into Hon Chay Mountain, a 2,752 foot (839m) mountain peak near Da Nang, Quang Nam Province, South Vietnam. All three crew members were killed. They included LCDR George W. Alexander, LCDR Roger H. Mullins, and ATC William M. Newton. [Taken from aviation-safety.net and other web sources] (WKillian, vvmf.org)

Silent Miles Summary

Leave a Reply